One post below is my version of radiant pluralism, inspired by David Shapiro's talk of yesterday. It's not how he would say it, exactly, but it's my translation into Mayhewese, which I speak fluently. All opinions are strictly my own: it's my application of what he said, in my own realm.

I could never reproduce his style of talk. It's digressive, but in a meaningful way--it always gets quickly enough to the point behind the point behind the point. It is extremely allusive and citational. Quotes from others will be performed in the appropriate voices and accents. Meyer Schapiro will appear every five to ten minutes. There were a lot of references to Kenneth Koch, John Cage, DeKooning, Darwin, and about 100 other people. The seminar itself was just an hour and a half segment of the 16 hour seminar that I was privileged to see. He also educated (spontaneously) some Kansas city museum goers on Rothko and De Kooning.

Email me at jmayhew at ku dot edu

"The very existence of poetry should make us laugh. What is it all about? What is it for?"

--Kenneth Koch

“El subtítulo ‘Modelo para armar’ podría llevar a creer que las

diferentes partes del relato, separadas por blancos, se proponen como piezas permutables.”

30 mar 2006

[update: moving to front]

I need a second list, this time of 100 poets who did not make the first list, because of my insufficient knowledge of them, my ambivalence--innumerable reasons, really... Maybe I just don't know the poet's first name. This list may be more fun to draw up--less pressure. These are just poets I've taken an interest in at some point. Maybe I've just loved one or two of their poems. Some are personal friends like Juan Carlos Mestre and Geoffrey Chaucer.

I've noticed something: very few of the poets in KK's RWDYGTR? are missing from among my own favorites. Koch did not appear to like much bad poetry.

This list is not a canon: it is expandable up to the limits of my own knowledge: I'm sure I will do a third hundred soon. Plus, it is valid only for JM. I'm not going to put Stefan George on it, because I haven't read him. I would never say he's not canonical for German poetry.

Blanca Andreu. David Antin. Rae Armantrout. María Victoria Atencia. Charles Bernstein. Anselm Berrigan. John Berryman. Elizabeth Bishop. David Bromige. Michael Brownstein.

Buson. John Cage. Guillermo Carnero. Luisa Castro. Geoffrey Chaucer. Isla Correyero. John Donne. Garcilaso de la Vega. Thomas Fink. Nada Gordon.

Thom Gunn. Menchu Gutiérrez. Robert Hayden. Lyn Hejinian. Anthony Hecht. Miguel Hernández. Friedrich Hölderlin. Susan Howe. David Huerta. Amalia Iglesias.

James Joyce. Maryrose Larkin. D.H. Lawrence. Frank Lima. Jorge Manrique. Harry Mathews. Jonathan Mayhew. Juan Carlos Mestre. Kasey Silem Mohammad. Eugenio Montejo.

Marianne Moore. Sawako Nakayasu. Gérard de Nerval. Alejandro Oliveros. Octavio Paz. Saint-John Perse. Sylvia Plath. Po Chu-I. Marcel Proust. Jorge Riechmann.

Theodore Roethke. Queneau. Pierre de Ronsard. Ana Rossetti. Leslie Scalapino. Christopher Smart. Arthur Sze. Gilbert Sorrentino. James Tate. Dylan Thomas.

Tony Towle. David Trinidad. Paul Valéry. Paul Verlaine. Thomas Waller. Wang Wei. Lewis Warsh. Ludwig Wittgenstein. James Wright. Richard Wright.

Louis Zukofksy.

I need a second list, this time of 100 poets who did not make the first list, because of my insufficient knowledge of them, my ambivalence--innumerable reasons, really... Maybe I just don't know the poet's first name. This list may be more fun to draw up--less pressure. These are just poets I've taken an interest in at some point. Maybe I've just loved one or two of their poems. Some are personal friends like Juan Carlos Mestre and Geoffrey Chaucer.

I've noticed something: very few of the poets in KK's RWDYGTR? are missing from among my own favorites. Koch did not appear to like much bad poetry.

This list is not a canon: it is expandable up to the limits of my own knowledge: I'm sure I will do a third hundred soon. Plus, it is valid only for JM. I'm not going to put Stefan George on it, because I haven't read him. I would never say he's not canonical for German poetry.

Blanca Andreu. David Antin. Rae Armantrout. María Victoria Atencia. Charles Bernstein. Anselm Berrigan. John Berryman. Elizabeth Bishop. David Bromige. Michael Brownstein.

Buson. John Cage. Guillermo Carnero. Luisa Castro. Geoffrey Chaucer. Isla Correyero. John Donne. Garcilaso de la Vega. Thomas Fink. Nada Gordon.

Thom Gunn. Menchu Gutiérrez. Robert Hayden. Lyn Hejinian. Anthony Hecht. Miguel Hernández. Friedrich Hölderlin. Susan Howe. David Huerta. Amalia Iglesias.

James Joyce. Maryrose Larkin. D.H. Lawrence. Frank Lima. Jorge Manrique. Harry Mathews. Jonathan Mayhew. Juan Carlos Mestre. Kasey Silem Mohammad. Eugenio Montejo.

Marianne Moore. Sawako Nakayasu. Gérard de Nerval. Alejandro Oliveros. Octavio Paz. Saint-John Perse. Sylvia Plath. Po Chu-I. Marcel Proust. Jorge Riechmann.

Theodore Roethke. Queneau. Pierre de Ronsard. Ana Rossetti. Leslie Scalapino. Christopher Smart. Arthur Sze. Gilbert Sorrentino. James Tate. Dylan Thomas.

Tony Towle. David Trinidad. Paul Valéry. Paul Verlaine. Thomas Waller. Wang Wei. Lewis Warsh. Ludwig Wittgenstein. James Wright. Richard Wright.

Louis Zukofksy.

I can be a pluralist and still dislike a good deal, still express that dislike in strong terms. Does anyone think of him or herself as having narrow taste? It is highly unlikely. Everyone knows you're supposed to have broad taste.

So my taste is extremely broad. There is no historical period or geographical region I reject. Of course, it's also *clustered* in certain areas, with clusters inside the clusters. I do prefer Japanese, Chinese, American, South American, Carribean, and West European poetries. I like ancient and modern, with some medieval thrown in. I like Basho and Issa too. Koch and Schuyler.

I like elite styles, neo-baroques, various neo-classicisms from Racine to Pope, romanticisms, and avant-gardes. I also like popular stuff: traditional balladry, Robert Burns, and Elizabethan song. I'm fond of Lorenz Hart and Johnny Mercer, Ira Gershwin and other Tin Pan Alley lyricists, Po Chu I. I like canonical things and things that are hot off the presses.

I'm not strongly a fan of contemporary free verse lyric confession, Tennyson or even Browning, Spanish neo-classicism, Oscar Hammerstein, or Bob Dylan. I don't like Benedetti, Lowell (Robert or Amy), Russell Edson, Phlip Larkin, Norman Dubie. I see these gaps as insignificant in the larger scheme of things. There are good poets I don't like (Browning, Larkin), and other poets I don't like who are pretty insignificant from a historical perspective (Armando Palacio Valdés.)

I'd like to write the defense of the uncommon reader. The common reader likes poetry from A to A-and-a-half. Pinsky through Collins. The uncommon reader likes poetry from A to beyond Z, with a few gaps along the way. Honestly speaking, nobody likes everything anyway. Don't pretend Pinsky through Collins through Gluck is the entire universe of poetry, or even one one-hundreth part of it. I'd much rather be an uncommon reader because, frankly, there are no limits except time, and not knowing Rumanian and Hungarian and 100 other languages.

So my taste is extremely broad. There is no historical period or geographical region I reject. Of course, it's also *clustered* in certain areas, with clusters inside the clusters. I do prefer Japanese, Chinese, American, South American, Carribean, and West European poetries. I like ancient and modern, with some medieval thrown in. I like Basho and Issa too. Koch and Schuyler.

I like elite styles, neo-baroques, various neo-classicisms from Racine to Pope, romanticisms, and avant-gardes. I also like popular stuff: traditional balladry, Robert Burns, and Elizabethan song. I'm fond of Lorenz Hart and Johnny Mercer, Ira Gershwin and other Tin Pan Alley lyricists, Po Chu I. I like canonical things and things that are hot off the presses.

I'm not strongly a fan of contemporary free verse lyric confession, Tennyson or even Browning, Spanish neo-classicism, Oscar Hammerstein, or Bob Dylan. I don't like Benedetti, Lowell (Robert or Amy), Russell Edson, Phlip Larkin, Norman Dubie. I see these gaps as insignificant in the larger scheme of things. There are good poets I don't like (Browning, Larkin), and other poets I don't like who are pretty insignificant from a historical perspective (Armando Palacio Valdés.)

I'd like to write the defense of the uncommon reader. The common reader likes poetry from A to A-and-a-half. Pinsky through Collins. The uncommon reader likes poetry from A to beyond Z, with a few gaps along the way. Honestly speaking, nobody likes everything anyway. Don't pretend Pinsky through Collins through Gluck is the entire universe of poetry, or even one one-hundreth part of it. I'd much rather be an uncommon reader because, frankly, there are no limits except time, and not knowing Rumanian and Hungarian and 100 other languages.

Many people think that the pressure to do something new in criticism is damaging--the demand for novelty and originality. After all, the argument goes, it's too much pressure to ask a young person to come up with an original approach to Dickens.

But what is the alternative? Doing something that's already been done?

I think there's a fallacy here: the idea that, with a limited canon, there are only so many things to be said about works of literature. Won't we run out of things to say after a certain point?

I have always felt the opposite: that hardly anything has been said about many, many authors, canonical or not. Plus, it is a fallacy to think that the number of authors is limited. There is very limited criticism on Clark Coolidge--a complex and major figure. I could think of maybe 100 other examples of things that are "understudied." And that's just me, off the top of my head.

But what is the alternative? Doing something that's already been done?

I think there's a fallacy here: the idea that, with a limited canon, there are only so many things to be said about works of literature. Won't we run out of things to say after a certain point?

I have always felt the opposite: that hardly anything has been said about many, many authors, canonical or not. Plus, it is a fallacy to think that the number of authors is limited. There is very limited criticism on Clark Coolidge--a complex and major figure. I could think of maybe 100 other examples of things that are "understudied." And that's just me, off the top of my head.

David's visit was a big success. His seminar on Radiant Pluralism was quite brilliant. We did it as an interview, but it turned into a wonderful improvised and highly digressive monologue with a few questions interrupting him from time to time. His reading in the evening charmed my undergraduate students who attended. As I am to my least prepared graduate students (more erudite, etc...), David Shapiro is to me. That's not quite right... I am better at David at one thing: I will beat him in a reticence contest any day.

29 mar 2006

28 mar 2006

Is literature something that belongs to a nation, a cultural patrimony? That's implicit in my field, which is based on the literature of a single modern nation state--even projected back before Spain was a nation in the modern sense. With different "nationalities" within contemporary Spain things get very complicated. Can Galician literature be about anything more than Galician cultural/national identity? (about in two sense: that's the subject of the works themselves, and that's the question posed by the very existence of such a thing.)

It's implicit in Comparative Literature--the "comparison" is between or among "national" traditions.

With Latin American lit at least there is an entire continent, with several regions, nations within these regions, etc... So the field doesn't get defined that way. There are still Mexicanists and colombianistas, of course, but they never get the entire field to themselves.

It's implicit in American Literature--that the implicit question, always, is what makes it American. Some American writers are more American than others. Emerson, Whitman, Williams, Melville.

I never thought I was that interested in this question. That is, I never really liked the idea of literature as belonging to someone's project of what the nation should be--whether it is right or left wing project or somewhere in between. Yet it is hard to step around such a big elephant. It is the displinary organization and ideology, all wrapped up in one package. It has to be unpacked.

It's implicit in Comparative Literature--the "comparison" is between or among "national" traditions.

With Latin American lit at least there is an entire continent, with several regions, nations within these regions, etc... So the field doesn't get defined that way. There are still Mexicanists and colombianistas, of course, but they never get the entire field to themselves.

It's implicit in American Literature--that the implicit question, always, is what makes it American. Some American writers are more American than others. Emerson, Whitman, Williams, Melville.

I never thought I was that interested in this question. That is, I never really liked the idea of literature as belonging to someone's project of what the nation should be--whether it is right or left wing project or somewhere in between. Yet it is hard to step around such a big elephant. It is the displinary organization and ideology, all wrapped up in one package. It has to be unpacked.

27 mar 2006

26 mar 2006

At the risk of boring my primary constituency, poets who aren't necessarily academics like I am, these are my criteria for a critical, academic article. This is what I try to achieve when I write, and the criteria I apply when refereeing an article for a journal. The article must address a critical problem of some significance, demonstrate critical primacy, and speak with an original voice.

Problem The article must first address a significant critical problem. That is, it cannot be merely informative or descriptive, but must make an argument. For me, the critical problem usually involves a paradox. For example, we know that Creeley's poetry was influenced by Pound and Williams. Yet, in comparison to their work or Denise Levertov's, his poetry is not strongly visual in the same way. A paradox is like a wrinkle in the fabric of our expectations, or a distance between what most people think about a particular writer and what is *actually* the case. I had an interesting talk with Mark Halliday: his perception of Thank You was that it contained many difficult poems that did not make sense on the surface. My perception of it was the opposite. Of course, when we got out the Collected Poems I saw that we had both overestimated the proportion of "easy" and "difficult" poems in the book, overlooking the ones that did not confirm our previous bias.

The critic must feel that the problem is of some significance and make a case for this significance. Does literary history change if Creeley is not a visual poet? Maybe it does. Maybe not. There has to be a non-obvious consequence that makes a difference for something else.

Primacy

The critical article cannot repeat what has been said before. It cannot argue an obvious thesis, that Levertov derives her line-breaks from WCW. It has to take into account what has already been written and enter into a critical dialogue with it. Even if not much has been written about the topic, there must be some demonstration of the gap in the critical literature.

Voice

The critic must speak with voice of her / his own. It can't be the application of an already existing critical discourse. The critical voice is the authority--not the literary theorist to whom the critic is beholden. Nobody else could have written this article but him / her / me / you.

***

I haven't said anything about theory. That is because the presence or absence of theory in the article (i.e. references to specific works by "name" theorists) is not directly relevant to these criteria. For me, the theory will usually be more implicit than explicit, simply because I have my own voice, more or less. Barthes is not theoretical because he quotes other theorists or presents abstract ideas (although he does do this too) but because his is an interesting mind dealing with critical problems. I find my own ideas more valuable than applications of Derridean theory, say, to a particular text. The silliest idea in my head is worth more than the most profound idea in someone else's head (Frank O'Hara, as paraphrased by Kenneth Koch). This is not arrogance. It is the starting principle. Why should you listen to me if I'm simply a less accomplished version of someone else?

Good academic criticism has to be extremely imaginative. It should convey the same excitement we get when we read Barthes on LaRochefoucauld. I hate "imaginative" criticism where I feel the critic is simply making things up. After all, making things up is pretty easy to do. That's cheating, in my mind. You can't say you'd "rather be interesting than right." You'll end up being interesting in a kind of dull way. If you stretch out a little bit, you have to have the smoking gun, the piece of evidence that makes your argument not only possible or plausible but probable. We've had students who seem to have the "spark" but can't quite put things together in a cogent way. I've been that student myself.

Bad criticism is bad because there are not that many people who can do all of this and put it together. Ever read a plodding, descriptive dissertation, where the dissertator seems to be merely going through the motions? He is not incompetent; he deserves the doctorate and a place in the profession, perhaps.

For myself, I feel that I need to have something for the formalist reader and something for the cultural critic at the same time. That is, if I'm writing about poetry there has to be something interesting going on in what I'm saying about the poetry, as poetry. At the same time there's got to be some other point beyond this as well--some reason for you to care even if you don't care about the poetry as poetry.

***

Don't bring your second-best arguments to Bemsha Swing. I don't have much tolerance for that.

Problem The article must first address a significant critical problem. That is, it cannot be merely informative or descriptive, but must make an argument. For me, the critical problem usually involves a paradox. For example, we know that Creeley's poetry was influenced by Pound and Williams. Yet, in comparison to their work or Denise Levertov's, his poetry is not strongly visual in the same way. A paradox is like a wrinkle in the fabric of our expectations, or a distance between what most people think about a particular writer and what is *actually* the case. I had an interesting talk with Mark Halliday: his perception of Thank You was that it contained many difficult poems that did not make sense on the surface. My perception of it was the opposite. Of course, when we got out the Collected Poems I saw that we had both overestimated the proportion of "easy" and "difficult" poems in the book, overlooking the ones that did not confirm our previous bias.

The critic must feel that the problem is of some significance and make a case for this significance. Does literary history change if Creeley is not a visual poet? Maybe it does. Maybe not. There has to be a non-obvious consequence that makes a difference for something else.

Primacy

The critical article cannot repeat what has been said before. It cannot argue an obvious thesis, that Levertov derives her line-breaks from WCW. It has to take into account what has already been written and enter into a critical dialogue with it. Even if not much has been written about the topic, there must be some demonstration of the gap in the critical literature.

Voice

The critic must speak with voice of her / his own. It can't be the application of an already existing critical discourse. The critical voice is the authority--not the literary theorist to whom the critic is beholden. Nobody else could have written this article but him / her / me / you.

***

I haven't said anything about theory. That is because the presence or absence of theory in the article (i.e. references to specific works by "name" theorists) is not directly relevant to these criteria. For me, the theory will usually be more implicit than explicit, simply because I have my own voice, more or less. Barthes is not theoretical because he quotes other theorists or presents abstract ideas (although he does do this too) but because his is an interesting mind dealing with critical problems. I find my own ideas more valuable than applications of Derridean theory, say, to a particular text. The silliest idea in my head is worth more than the most profound idea in someone else's head (Frank O'Hara, as paraphrased by Kenneth Koch). This is not arrogance. It is the starting principle. Why should you listen to me if I'm simply a less accomplished version of someone else?

Good academic criticism has to be extremely imaginative. It should convey the same excitement we get when we read Barthes on LaRochefoucauld. I hate "imaginative" criticism where I feel the critic is simply making things up. After all, making things up is pretty easy to do. That's cheating, in my mind. You can't say you'd "rather be interesting than right." You'll end up being interesting in a kind of dull way. If you stretch out a little bit, you have to have the smoking gun, the piece of evidence that makes your argument not only possible or plausible but probable. We've had students who seem to have the "spark" but can't quite put things together in a cogent way. I've been that student myself.

Bad criticism is bad because there are not that many people who can do all of this and put it together. Ever read a plodding, descriptive dissertation, where the dissertator seems to be merely going through the motions? He is not incompetent; he deserves the doctorate and a place in the profession, perhaps.

For myself, I feel that I need to have something for the formalist reader and something for the cultural critic at the same time. That is, if I'm writing about poetry there has to be something interesting going on in what I'm saying about the poetry, as poetry. At the same time there's got to be some other point beyond this as well--some reason for you to care even if you don't care about the poetry as poetry.

***

Don't bring your second-best arguments to Bemsha Swing. I don't have much tolerance for that.

25 mar 2006

Rhyme nowadays seems relegated to

humorous verse

writing for children

popular songs

political reactionaries and new formalists

the past

etc... So that means there's a demarcation of poetry, that's of the present, non-humorous, not for children, not popular. There's a certain puritanism, an embarrassment even. Anything causing this much embarrassment has to have something going for it. I'm embarrassed by it myself!

humorous verse

writing for children

popular songs

political reactionaries and new formalists

the past

etc... So that means there's a demarcation of poetry, that's of the present, non-humorous, not for children, not popular. There's a certain puritanism, an embarrassment even. Anything causing this much embarrassment has to have something going for it. I'm embarrassed by it myself!

23 mar 2006

From Jordan, an uncharacterstically enraged post. I'm glad I'm not the only one taken to fits of pique: I am grasping to think of a more horrifying document of poetic arrogance than Christian Wiman's editorial in the March issue of Poetry. Michael Dumanis's sniveling journal for the magazine's website in which he refers with amazement that a student of his, not one of the better ones, actually had an insight -- less hateful than this.

Here's a choice bit from Wiman's foul pen:

"Not that we say any of this in our responses to the last group, of course. No, that would be presumptuous; we fall back on the generic language of rejection. "We have been very glad to read these poems," we say, by which we mean that it is a good thing for survivors to send such work along to editors, because who knows what might happen, and it is a good thing for us to have our hopes awoken, our complacencies tested. "These poems have moved us," we say, meaning the blunt fact of them, the failure of them [emphasis Jordan Davis], the reminder they give of how much human endeavor, in human terms, comes to nought. "But we're not going to be able to use the poems at this time," we conclude, and mean exactly that, for who knows, perhaps one of these manuscripts will not be burned or buried but instead preserved, passed along to the poet's children, then to his children's children. Perhaps one of these very bundles will make its way into our offices again in a hundred years, when we shall all be changed."

Here's a choice bit from Wiman's foul pen:

"Not that we say any of this in our responses to the last group, of course. No, that would be presumptuous; we fall back on the generic language of rejection. "We have been very glad to read these poems," we say, by which we mean that it is a good thing for survivors to send such work along to editors, because who knows what might happen, and it is a good thing for us to have our hopes awoken, our complacencies tested. "These poems have moved us," we say, meaning the blunt fact of them, the failure of them [emphasis Jordan Davis], the reminder they give of how much human endeavor, in human terms, comes to nought. "But we're not going to be able to use the poems at this time," we conclude, and mean exactly that, for who knows, perhaps one of these manuscripts will not be burned or buried but instead preserved, passed along to the poet's children, then to his children's children. Perhaps one of these very bundles will make its way into our offices again in a hundred years, when we shall all be changed."

The Red Robins is wonderful. It is on my 10 top novels of all time list. I think, though, you already haved to be immersed in Kenneth Koch's world to even read it, let alone appreciate it. It's parody, but of what?

a certain genre of children's adventure novel?

Noh theater?

American intervention in Vietnam?

epic poetry?

all or none of the above?

I love it for every fifth chapter that stands on its on as a wonderful prose/poetry vignette--even if it weren't part of a novel. I haven't figured out if the novel is actually a novel--as though that mattered. This and Harry Mathews My Life in CIA, which I am also reading by perfect coincidence, are the perfect pair of novels to understand the absurd conjunction of Cold War Politics and avant-garde poetics, as filtered through a particular kind of American naiveté. The locus solus travel agency is the paradigmatic image. The central figures in each book are the prototypical American innocents abroad (Henry James). You can use that for your term papers, children. Just send me a check for $200 and the idea is yours.

a certain genre of children's adventure novel?

Noh theater?

American intervention in Vietnam?

epic poetry?

all or none of the above?

I love it for every fifth chapter that stands on its on as a wonderful prose/poetry vignette--even if it weren't part of a novel. I haven't figured out if the novel is actually a novel--as though that mattered. This and Harry Mathews My Life in CIA, which I am also reading by perfect coincidence, are the perfect pair of novels to understand the absurd conjunction of Cold War Politics and avant-garde poetics, as filtered through a particular kind of American naiveté. The locus solus travel agency is the paradigmatic image. The central figures in each book are the prototypical American innocents abroad (Henry James). You can use that for your term papers, children. Just send me a check for $200 and the idea is yours.

22 mar 2006

Out with Roethke and Thomas, in with Drew Gardner and Apollinaire. Any more vulnerable poets in the list of 100?

***

My goal was to write one full-length, 5,000 word academic article each month during 2006. This is probably impossible. I've done two so far, finishing one today. The third, which will not be finished by the end of March, exists in four separate versions:

*a learnéd epilogue to Kenneth Koch's "Some South American Poets"

*a conference paper read at the AWP to thunderous applause

*a paper given in the Poetics Seminar, University of Kansas, to the thunderous applause of five people

*a draft of a scholarly article, incomplete and without footnotes and bibliography, hence not very scholarly

And they say conferences should help stimulate research. Well, yes and no. The extra effort of moving sentences around between these four documents is certainly slowing me down.

***

Charles Rosen points out in the NYRB that you can't make sense of music without advocating for it, and that the refusal to make sense of it is a kind of implicit condemnation. How true this is, and not just of music.

***

It goes without saying that each article I write should be substantive and excellent, advocating passionately for a particular kind of poetics. Some colleagues of mine in the "profession" refer to a certain kind of publications as "bird droppings." Insubtantial articles scattered here and there.

***

My goal was to write one full-length, 5,000 word academic article each month during 2006. This is probably impossible. I've done two so far, finishing one today. The third, which will not be finished by the end of March, exists in four separate versions:

*a learnéd epilogue to Kenneth Koch's "Some South American Poets"

*a conference paper read at the AWP to thunderous applause

*a paper given in the Poetics Seminar, University of Kansas, to the thunderous applause of five people

*a draft of a scholarly article, incomplete and without footnotes and bibliography, hence not very scholarly

And they say conferences should help stimulate research. Well, yes and no. The extra effort of moving sentences around between these four documents is certainly slowing me down.

***

Charles Rosen points out in the NYRB that you can't make sense of music without advocating for it, and that the refusal to make sense of it is a kind of implicit condemnation. How true this is, and not just of music.

***

It goes without saying that each article I write should be substantive and excellent, advocating passionately for a particular kind of poetics. Some colleagues of mine in the "profession" refer to a certain kind of publications as "bird droppings." Insubtantial articles scattered here and there.

19 mar 2006

We have a bias toward the contemporary in some sense, in that we overvalue some work of our own period. And we also have a bias against the contemporary: we don't really believe that any contemporary writer belongs on the same list as Ovid. [For we read "I."] That makes lists like the one below very tricky.

18 mar 2006

My 100 favorite poets. A list in progress. In alphabetical order. Once I get to 100 I will start revising. A poet can be kicked off the list if I remember I like another better. Why do I like silly lists like this? This is my "team." These poets have my back, so to speak; I can call on them for help at any time. At least one of them will be able to help me out of a jam. The final list will also give a completely accurate vision of who I am.

[UPDATE: What I've learned is that my taste is very conventionally canonical. Any eccentricity is at the very edges of the list. Take a way a Catalan poet and a few minor poets of the New York School, and my list looks very much like the canon. The only unconventionality is in the omissions, quite possibly. It's also true that I don't have much space left over for the Charles Wrights of the world. The Dave Smiths and Charles Simics. I'm not trying to denigrate such poets, but I just don't feel them to be among my personal top 100. I'm not even sure if Andrew Marvell will make the list, so don't ask me about Gregory Orr or Mark Strand.]

[UPDATE 2: 97. I have 3 more to go. Roethke and Dylan Thomas are the ones that might have to go soon. Do I really even like these poets? Each one of these poets sings in a different key.]

[UPDATE 3: 100. Now begin the revisions, where I eliminate the 10 poets I like least and add another 10]

Vicente Aleixandre. Guiillaume Apollinaire. John Ashbery. W.H. Auden. Basho. Charles Baudelaire. Samuel Beckett. Ted Berrigan. William Blake. Jorge Luis Borges.

Coral Bracho. André Breton. William Bronk. Lord Byron. Thomas Campion. Catullus. Constantine Cavafy. Paul Celan. Joseph Ceravolo. Luis Cernuda.

René Char. John Clare. Clark Coolidge. Hart Crane. Robert Creeley. E.E. Cummings. HD. Dante. Jordan Davis. Emily Dickinson.

T.S. Eliot. Robert Frost. Antonio Gamoneda. Concha García. Federico García Lorca. Drew Gardner. Pere Gimferrer. Allen Ginsberg. Luis de Góngora. Barbara Guest.

Jorge Guillén. Thomas Hardy. Robert Herrick. Homer. Horace. Fanny Howe. Issa. Lisa Jarnot. Juan Ramón Jiménez.

Ronald Johnson.

John Keats. Jack Kerouac. Kenneth Koch. José Lezama Lima. Fray Luis de León. Antonio Machado. Jackson Mac Low. Stéphane Mallarmé. Vladimir Mayakvosky. Bernadette Mayer.

Jess Mynes. Lorine Niedecker. Pablo Neruda. Alice Notley. Frank O'Hara. Ovid. Ron Padgett. Leopoldo María Panero. Li Po. Fernando Pessoa.

Petrarch. Francis Ponge. Ezra Pound. "Psalms." Francisco de Quevedo. Pierre Reverdy. Rainier Maria Rilke. Arthur Rimbaud. Claudio Rodríguez. Jerome Rothenberg.

Raymond Roussel. Pedro Salinas. James Schuyler. William Shakespeare. David Shapiro. P.B. Shelley. Ron Silliman. Jack Spicer. Gertrude Stein. Wallace Stevens.

Tu Fu. José Angel Valente. César Vallejo. Blanca Varela. Lola Velasco. Walt Whitman. William Carlos Williams. Wyatt. W.B. Yeats. Juan de Yépez (alias Saint John of the Cross).

[UPDATE: What I've learned is that my taste is very conventionally canonical. Any eccentricity is at the very edges of the list. Take a way a Catalan poet and a few minor poets of the New York School, and my list looks very much like the canon. The only unconventionality is in the omissions, quite possibly. It's also true that I don't have much space left over for the Charles Wrights of the world. The Dave Smiths and Charles Simics. I'm not trying to denigrate such poets, but I just don't feel them to be among my personal top 100. I'm not even sure if Andrew Marvell will make the list, so don't ask me about Gregory Orr or Mark Strand.]

[UPDATE 2: 97. I have 3 more to go. Roethke and Dylan Thomas are the ones that might have to go soon. Do I really even like these poets? Each one of these poets sings in a different key.]

[UPDATE 3: 100. Now begin the revisions, where I eliminate the 10 poets I like least and add another 10]

Vicente Aleixandre. Guiillaume Apollinaire. John Ashbery. W.H. Auden. Basho. Charles Baudelaire. Samuel Beckett. Ted Berrigan. William Blake. Jorge Luis Borges.

Coral Bracho. André Breton. William Bronk. Lord Byron. Thomas Campion. Catullus. Constantine Cavafy. Paul Celan. Joseph Ceravolo. Luis Cernuda.

René Char. John Clare. Clark Coolidge. Hart Crane. Robert Creeley. E.E. Cummings. HD. Dante. Jordan Davis. Emily Dickinson.

T.S. Eliot. Robert Frost. Antonio Gamoneda. Concha García. Federico García Lorca. Drew Gardner. Pere Gimferrer. Allen Ginsberg. Luis de Góngora. Barbara Guest.

Jorge Guillén. Thomas Hardy. Robert Herrick. Homer. Horace. Fanny Howe. Issa. Lisa Jarnot. Juan Ramón Jiménez.

Ronald Johnson.

John Keats. Jack Kerouac. Kenneth Koch. José Lezama Lima. Fray Luis de León. Antonio Machado. Jackson Mac Low. Stéphane Mallarmé. Vladimir Mayakvosky. Bernadette Mayer.

Jess Mynes. Lorine Niedecker. Pablo Neruda. Alice Notley. Frank O'Hara. Ovid. Ron Padgett. Leopoldo María Panero. Li Po. Fernando Pessoa.

Petrarch. Francis Ponge. Ezra Pound. "Psalms." Francisco de Quevedo. Pierre Reverdy. Rainier Maria Rilke. Arthur Rimbaud. Claudio Rodríguez. Jerome Rothenberg.

Raymond Roussel. Pedro Salinas. James Schuyler. William Shakespeare. David Shapiro. P.B. Shelley. Ron Silliman. Jack Spicer. Gertrude Stein. Wallace Stevens.

Tu Fu. José Angel Valente. César Vallejo. Blanca Varela. Lola Velasco. Walt Whitman. William Carlos Williams. Wyatt. W.B. Yeats. Juan de Yépez (alias Saint John of the Cross).

17 mar 2006

16 mar 2006

I haven't quite figured out the issue of periodicity on The Duplications. I don't get that many submissions, so I haven't found anything I really wanted to publish in the past few months. I really want to publish a few poems every week. Someone wrote

"Och som Lars påpekar har Jonathan Mayhew publicerat en del fina dikter på The Duplications."

Which I interpret to mean: "Also, Lars notes that Jonathan Mayhew has published a fine poet in The Duplications."

Of course, I don't even know what language this is. Swedish? Norwegian? Danish? So I'm sure my translation is off.

Janet Holmes; Like many of the NPR commentator-writers, he needs an educated audience; at the same time, there's an appeal to the audience that they're not snooty know-it-alls, they aren't pointy-head "academics," they're regular people who sit at their breakfast bars in the suburbs, listening to music from an entertainment center, letting the dog out--a mutt! not a purebred!--just wanting a good laugh, etc. The anti-intellectualism of the elite class. . That's such a perfect description of what I used to call the "middle-brow" before I learned people would give me endless grief for calling it that.

I like the way "selves" is plural in Frank O'Hara's poems: "my selves." That should be an inherently plural concept. What defines the human selves is a disjunctive continuity in time. I can still taste that humilition of 10 or 30 years ago. That is still me. Yet I still wake up each day surprised that I am still "myself." There's a sense of unreality surrounding this. The way César Vallejo can remember the day that he will die (future memory). Or Kenneth Koch can remember when he wrote "The Circus," in another poem of the same title. I've often have the feeling that a personality solidifies, hardens and becomes more dense, over time: it becomes more of what it already always was. So there's a fundamental tension between the self as Protean and discontinuous and the self as essentially itself, and more so all the time.

The experience of finding something one has written, recognizing the text as one's own, but without any specific memory of the thoughts behind the writing. As though it were written by someone else. Borges meeting a former self on a park bench in Geneva. Is this what Piombino means by time travel?

The experience of finding something one has written, recognizing the text as one's own, but without any specific memory of the thoughts behind the writing. As though it were written by someone else. Borges meeting a former self on a park bench in Geneva. Is this what Piombino means by time travel?

15 mar 2006

Ran into Cyrus Console in student union coffee place. Gave him some pointers on Spanish versification. And that was right after I told him to stop calling me professor Mayhew! I was right back in professorial mode. I gave him the AWP scoop too.

I was wondering why the English Department was not showing up to Poetics Seminar en masse. Well, it turns out that for some people, actually having ideas about poetry and meeting to discuss them is threatening to their idea of "poetry." We do have Cyrus himself, and Ken Irby, Joe Harrington, as regulars. That should be enough for me [sigh]. Two of my regulars from Spanish and French are chairs of their department--in one case a new mother as well--so they cannot come very much.

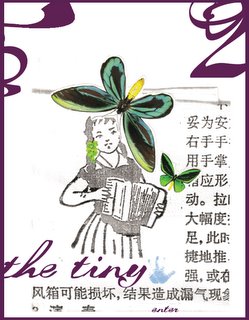

Got my copy of The Tiny today. Nice collage by David on the cover, and the first poem is by him too. "Hapax Legomen."

Which means, I think, a word which only appears once in a particular language or corpus of texts. It seems to be contradictory to the very idea of language, to have a word that appears only once. There cannot be a unique word.

Have you bought your plane ticket yet, David Shapiro?

The one subject that is dullest to non-poets, but most fascinating to poets themselves? (Except those who find it dull anyway.)

When trying to read more is like having a full meal when you are not hungry in the least.

Jordan who said the AWP was a way of spending a few days without seeing poetry. What delicious irony. No poetry is seen, only heard. The poets themselves gain visibility, corporality.

It's always feast and famine at the same time. There is always too much and not enough.

I'm trying to read a book called The Dominion of the Dead by Robert Pogue Harrison. Whenever I pick it up and read a few sentences I think: "Henry Gould would enjoy this book more than I ever could." I'm sure it's quite brilliant, but it has nothing to say to me today.

"We no longer think of the house in the ancient way; yet even if we find it difficult to phrase exactly how we do think of it, we nevertheless know, more or less, what we want or need or expect from our houses."

He goes on to say that houses have windows and tombs don't. Well yes. This could be great, but not today.

Jordan who said the AWP was a way of spending a few days without seeing poetry. What delicious irony. No poetry is seen, only heard. The poets themselves gain visibility, corporality.

It's always feast and famine at the same time. There is always too much and not enough.

I'm trying to read a book called The Dominion of the Dead by Robert Pogue Harrison. Whenever I pick it up and read a few sentences I think: "Henry Gould would enjoy this book more than I ever could." I'm sure it's quite brilliant, but it has nothing to say to me today.

"We no longer think of the house in the ancient way; yet even if we find it difficult to phrase exactly how we do think of it, we nevertheless know, more or less, what we want or need or expect from our houses."

He goes on to say that houses have windows and tombs don't. Well yes. This could be great, but not today.

The NCAA tournament is replete with the poetic function. We have alliteration: March Madness, Final Four, Elite Eight, Sweet Sixteen. Metaphor and pun (big dance, sweet sixteen). Neologism: bracketology. It's an amateur's delight, since few of us know more than a few teams in any detail. It has uncertainty and chance, which is always an inherently poetic quality, and is inherently *arguable.* The idea that it reduces "productivity" is certainly absurd. Such an infusion of poetry into the workplace can only have beneficial effects.

14 mar 2006

Horses, black. Black iron shoes.

On black capes, shining stains of ink and wax.

Lead skulls - they cannot weep.

Patent-leather souls - looming on the road.

Hunch-backed, nocturnal, wherever they move they ordain

dark rubber silences and fears of fine sand.

They go where they want, concealing in their heads

a vague astronomy of unreal guns.

***

I feel that approach might be better than the more conventional idea:

Black are the horses.

The horseshoes are black.

On their capes are glistening

stains of ink and wax...

These shorter lines often lead the translator pad, to add words, whereas if I try to cram two lines into one I tend to compress more.

On black capes, shining stains of ink and wax.

Lead skulls - they cannot weep.

Patent-leather souls - looming on the road.

Hunch-backed, nocturnal, wherever they move they ordain

dark rubber silences and fears of fine sand.

They go where they want, concealing in their heads

a vague astronomy of unreal guns.

***

I feel that approach might be better than the more conventional idea:

Black are the horses.

The horseshoes are black.

On their capes are glistening

stains of ink and wax...

These shorter lines often lead the translator pad, to add words, whereas if I try to cram two lines into one I tend to compress more.

Try to make a list of the 100 American poets you love best, in exact order.

Ok. Have you tried? It's impossible. You know Ezra Pound should be higher than #19. Ceravolo is in 6th place, but is this right? How can he beat out H.D.? The list folds in on itself endlessly. Is Frost #5 or #35? You dislike certain aspects of Eliot, Moore. Where does Frank Lima figure? What are the dimensions of your ignorance. Sorry, Robert Duncan, you are #89, right after #88, Robert Lowell. Roethke hovers in the mid thirties. Where do you place Jarnot and Gardner? Berrigan? Ron Padgett? Charles Olson? Schuyler? Bronk? Plath? What about the poets you are supposed to love, but don't?

There's no doubt about number one, however. It's Frank O'Hara.

Ok. Have you tried? It's impossible. You know Ezra Pound should be higher than #19. Ceravolo is in 6th place, but is this right? How can he beat out H.D.? The list folds in on itself endlessly. Is Frost #5 or #35? You dislike certain aspects of Eliot, Moore. Where does Frank Lima figure? What are the dimensions of your ignorance. Sorry, Robert Duncan, you are #89, right after #88, Robert Lowell. Roethke hovers in the mid thirties. Where do you place Jarnot and Gardner? Berrigan? Ron Padgett? Charles Olson? Schuyler? Bronk? Plath? What about the poets you are supposed to love, but don't?

There's no doubt about number one, however. It's Frank O'Hara.

Kindness to those with less power is condescension. Kindness to those with more power is ingratiation. So true kindness can only exist between equals? Or is that just rivalry and jockeying-for-position?

***

There is a kind of wound that cannot be confessed, because the public knowledge of the wound, how much it hurts, would be much worse than the wound itself. To be thought petty and confused...

***

There is a kind of wound that cannot be confessed, because the public knowledge of the wound, how much it hurts, would be much worse than the wound itself. To be thought petty and confused...

13 mar 2006

Tienen, por eso no lloran,

de plomo las calaveras.

Con el alma de charol

vienen por la carretera.

[Their skulls are lead--that's why they don't weep. With souls of patent leather come over the highway]

This de-humanizing moment comes toward the beginning of Lorca's "Romance de la guardia civil española." "Charol" is the material that famous tricornio hats is made of, so the souls of the guardia civil is made of the same material. The metonymy is made into a metaphor.

The guardia civil was founded in the late 19th century to patrol rural roads. It is a completely militarized police force, with a reputation for brutality. Since the gypsies were an itinerant, marginalized group, they were the natural target of this paramilitary force. In this poem they attack a gypsy settlement while the gypsies are putting on some kind of Christmas party. There are children dressed up as the Virgin and Saint Joseph. There is someone dressed up as Pedro Domecq, the local oligarch, here near the Southern Andalusian city of Jerez de la Frontera. (Detrás va Pedro Domecq / con tres sultanes de Persia.) You've probably drunk his products. ("Sherry" is how a British guy pronounces "Jerez.")

So it is the destruction of pure innocent imagination by pure depravity. There is no middle ground. The guardia civil went enthusiastically for the right during the civil war.

What's the Pope going to dress up in next?

We were struck by a tornado here yesterday morning. The only Sunday I've spent in Lawrence for quite some time, and a tornado strikes. I can't even get into my office since they've pretty much closed the campus down.

In good news, I suffered no damage to person, car, or apartment. We beat Texas and got a good seed in the March madness--#4 in what I see as a weaker side of the bracket.

In good news, I suffered no damage to person, car, or apartment. We beat Texas and got a good seed in the March madness--#4 in what I see as a weaker side of the bracket.

11 mar 2006

Just back from the AWP in Austin, and hanging out with people like Kasey, Anne B., Jordan, Jess, Lee Ann, Joshua Clover, Tony Robinson, Laurel, C. Dale, Kenneth Koch's son-in-law Mark Statman, Gina, Peter Gizzi, Jennifer Moxley, Danielle Pafunda, Chris (Edgar, co-editor of The Hat), Julie Dill, Shanna, Garrett, Josh Corey, Liz Willis, Reb L., Stephanie Young, Aaron Tieger, Aaron Belz, Mark Halliday, and numerous others. Some I met for the first time, like Gary Norris. Many I knew before. I met Eileen Myles, that was pretty cool. I even met Joe Massey.

There are only a few bloggers who have been blogging along with me since 2002 or 03 whom I have not yet met.

Didn't get to meet Tony Tost. I was sorely disappointed by that. They put two blogging panels in competition and I could only be one place at a time.

Josh Corey talks exactly like he writes in the Cahiers. In fact, he's the exact same person as he plays on line. This is comforting.

The Kenneth Koch panel was awesome. I seemed to have gone over well, and Jill's paper on Koch's pedagogical didactic side was brilliant, as were the other panelists. Just the combined insights of the five of us, I think, gave a sense of the depth and reach of Koch's work. I was happy to contribute just my small part to that.

If I didn't put your name in this list, it's not that I didn't like meeting you. I liked everyone I met, in fact. It just means I got back after an interminable plane trip and am exhausted.

There are only a few bloggers who have been blogging along with me since 2002 or 03 whom I have not yet met.

Didn't get to meet Tony Tost. I was sorely disappointed by that. They put two blogging panels in competition and I could only be one place at a time.

Josh Corey talks exactly like he writes in the Cahiers. In fact, he's the exact same person as he plays on line. This is comforting.

The Kenneth Koch panel was awesome. I seemed to have gone over well, and Jill's paper on Koch's pedagogical didactic side was brilliant, as were the other panelists. Just the combined insights of the five of us, I think, gave a sense of the depth and reach of Koch's work. I was happy to contribute just my small part to that.

If I didn't put your name in this list, it's not that I didn't like meeting you. I liked everyone I met, in fact. It just means I got back after an interminable plane trip and am exhausted.

8 mar 2006

Jim Behrle is usually right on target. It's not that I am too cowardly to take him to task for his "excesses," for fear of being a target myself, but that I agree with what he says. For example, he was completely correct about Kent Johnson, from day one. If I had listened to Jim earlier, I could have just spared myself more fruitless engagements with him.

He is on target on Silliman. Always has been. Ron takes it in stride because it's not really malicious.

What you don't know from people's blogs is if they are more or less assholic in real life than the asshole they play on the internet. Ultimately it all shakes down to the same thing, though. If I act like an asshole on the blog, don't think I'm a nice guy in non-blog life.

I could be flamed by others just for liking Jim. I don't think I'm being "courageous" either way. I'm not jumping into a burning building by expressing an opinion on a blog.

He is on target on Silliman. Always has been. Ron takes it in stride because it's not really malicious.

What you don't know from people's blogs is if they are more or less assholic in real life than the asshole they play on the internet. Ultimately it all shakes down to the same thing, though. If I act like an asshole on the blog, don't think I'm a nice guy in non-blog life.

I could be flamed by others just for liking Jim. I don't think I'm being "courageous" either way. I'm not jumping into a burning building by expressing an opinion on a blog.

"Ah de la vida." Nadie me responde....

"Ah de la casa" is what you would say if you you wanted to see if anyone was home. Something you shout out when entering a house. So "Ah de la vida" is saying: "anyone there? life?" Quevedo use of language is thoroughly "modern."

I should have been a scholar of 17th-century Spanish poetry. Somehow I got hung up on the bloody twentieth.

"presentes sucesiones de difuntos" --that's an interesting conception of human life: a sequence of successive individual present moments, each of which is inhabited by a different dead man, a "difunto."

***

Interesting in William Carlos Williams' essay on Lorca (this from '39): that Williams presents Lorca in terms of Spanish literary traditions, in a quite erudite way. The struggle and dialectic between popular and "culto" traditions. WCW brings in the Poema del Mío Cid, the romancero, baroque poetry, etc... but doesn't spend as much time on flamenco or gypsy traditions. Williams was condescended to for years by people vastly inferior to him in critical acumen. He was translating from the Spanish long before the boom in translations of the 60s. He knew of Neruda and Parra, Lorca, and the traditional Spanish cancionero.

"Ah de la casa" is what you would say if you you wanted to see if anyone was home. Something you shout out when entering a house. So "Ah de la vida" is saying: "anyone there? life?" Quevedo use of language is thoroughly "modern."

I should have been a scholar of 17th-century Spanish poetry. Somehow I got hung up on the bloody twentieth.

"presentes sucesiones de difuntos" --that's an interesting conception of human life: a sequence of successive individual present moments, each of which is inhabited by a different dead man, a "difunto."

***

Interesting in William Carlos Williams' essay on Lorca (this from '39): that Williams presents Lorca in terms of Spanish literary traditions, in a quite erudite way. The struggle and dialectic between popular and "culto" traditions. WCW brings in the Poema del Mío Cid, the romancero, baroque poetry, etc... but doesn't spend as much time on flamenco or gypsy traditions. Williams was condescended to for years by people vastly inferior to him in critical acumen. He was translating from the Spanish long before the boom in translations of the 60s. He knew of Neruda and Parra, Lorca, and the traditional Spanish cancionero.

7 mar 2006

Come hear me speak about Lorca tomorrow. If you want to read the paper, it is on the website. You'll need to know the password which I can give to you if you email me.

I am not sure where my anger comes from. I am tired of people attacking poetry I happen to like, and then turning around and claiming they are the ones with a broad, all-encompassing taste. They just care about the POETRY. There are no schools of POETRY, only POETRY, good or bad. That's fine, I agree--but then why turn around and declare large areas of the poetic field off-limits? Poetry that uses traditional modern techniques of parody, collage, pastiche, randomness, etc... (I say traditional because they have been around a long time already) doesn't count. It's not real poetry for these idiots. It doesn't "communicate" anything. Haven't we heard all this before? Isn't that what they said about The Tennis Court Oath?

So that's why I am declaring blog war on anyone who puts forward dumb arguments about poetry.

So that's why I am declaring blog war on anyone who puts forward dumb arguments about poetry.

6 mar 2006

Scofflaw asks what the 835th flarf poem might contribute. Presumably nothing. Maybe someone should have told Haydn to stop writing symphonies. Stop with the fugues already, Johann Sebastian! After all, what's "yet another" symphony or fugue going to add? Don't we have enough already? Yet it is easy to see how fallacious this argument is: there's no way of knowing what the next poem will be like. Maybe the 836th will be brilliant, followed by 100 more that don't contribute anything, then 10 that do. And so on. I'm wondering what the 100,000th "fishing trip with father" or "trying on grandmother's shoes" poem contributes to "serious examination of the human condition." Don't we already know about the "human condition" by now? Will a few more poems tell us the little we don't know? Like 100,027? Then we can all stop writing poems. The godamned human condition will be completely explored. That's just a tired phrase used by people with nothing substantive to say, to defend boring art. You know it's dull, because that's the only thing you can say about it: it explores the human condition.

It's kind of ironic that "835" would seem like a large number of poems in a particular style, when for twenty or thirty years a lot of poets in Iowa and Nebraska and Oregon and California have been writing hundreds of thousands of the same kind of flat, autobiographical lyric explorations of the human condition. When is it going to be enough? Wouldn't you need 10,000 flarf poems just to make a dent? Surely the argument from quantity is not a winning one for the enemies of flarf, unless the idea is that all flarf poems are just the same poem. But that's no more true of flarf than of anything else. Why didn't Petrarch stop after one or two sonnets? Aren't they all the same, really? Even if they were -- don't we want a lot of them anyway?

It's kind of ironic that "835" would seem like a large number of poems in a particular style, when for twenty or thirty years a lot of poets in Iowa and Nebraska and Oregon and California have been writing hundreds of thousands of the same kind of flat, autobiographical lyric explorations of the human condition. When is it going to be enough? Wouldn't you need 10,000 flarf poems just to make a dent? Surely the argument from quantity is not a winning one for the enemies of flarf, unless the idea is that all flarf poems are just the same poem. But that's no more true of flarf than of anything else. Why didn't Petrarch stop after one or two sonnets? Aren't they all the same, really? Even if they were -- don't we want a lot of them anyway?

Here's the deal about flarf, or language poetry, or anything for that matter. I don't care whether you like it or not. It's not some vegetable that will turn you into Popeye. There are a lot of things I don't like: Celtic folk music and Philip Larkin, for example. Many novels I teach in class are ones I don't particularly like. I just think it would be interesting or useful to teach a particular novel sometimes. What I like or dislike is not particuarly interesting, on the other hand. Why should it be? I like enough things to be pretty wide-ranging in my reading and listening, but I don't like everything either.

However, I do have a problem if you say that flarf is not adding anything to the conversation. That's just wrong. I do have a problem with you saying "real poets could not possibly be interested in flarf." That's as close to an error of *fact that an error of *judgment can come. Maybe you love the Chieftans. I am not banning you from the blog because of that. Everything's part of the conversation if you want it to be. I would never say: You don't need to know abou Philip Larkin. This woud be hypocrisy. After all, I know about him, why shouldn't you too?

There's also a point at which I lose patience with people who simply don't know very much about poetry. There's a reason we use a Greek word for "parody," which is that the Greeks had parody too. I know it's frightening to think that poetry has a long history with lots of genres, some lyrical and others satirical, elegiac, epistolary, etc... that it isn't just whatever a narrow sector of people want to agree it is, at some particular point in time.

However, I do have a problem if you say that flarf is not adding anything to the conversation. That's just wrong. I do have a problem with you saying "real poets could not possibly be interested in flarf." That's as close to an error of *fact that an error of *judgment can come. Maybe you love the Chieftans. I am not banning you from the blog because of that. Everything's part of the conversation if you want it to be. I would never say: You don't need to know abou Philip Larkin. This woud be hypocrisy. After all, I know about him, why shouldn't you too?

There's also a point at which I lose patience with people who simply don't know very much about poetry. There's a reason we use a Greek word for "parody," which is that the Greeks had parody too. I know it's frightening to think that poetry has a long history with lots of genres, some lyrical and others satirical, elegiac, epistolary, etc... that it isn't just whatever a narrow sector of people want to agree it is, at some particular point in time.

5 mar 2006

It Ain't Your Parents' Bad Poetry, But...:

"Those of you who write *actual* poetry will probably not be familiar with the term "flarf," and will undoubtedly *not* find it rewarding to be enlightened on the subject."

This is closed-minded and presumes quite a bit. It is the very exemplification of closed-mindedness. Not only are these readers presumed not to know about flarf, but they are presumed not to be the least bit curious. If you write *real poetry, you won't be interested in a particular parodic form of poetry that has emerged recently. Huh? Why not? I imagine some people who prefer more mainstream work will think flarf is a hoot , or a valuable contribution to poetry, and others won't.

The argument from ignorance: "desprecia cuanto ignora" as Machado would say.

"Those of you who write *actual* poetry will probably not be familiar with the term "flarf," and will undoubtedly *not* find it rewarding to be enlightened on the subject."

This is closed-minded and presumes quite a bit. It is the very exemplification of closed-mindedness. Not only are these readers presumed not to know about flarf, but they are presumed not to be the least bit curious. If you write *real poetry, you won't be interested in a particular parodic form of poetry that has emerged recently. Huh? Why not? I imagine some people who prefer more mainstream work will think flarf is a hoot , or a valuable contribution to poetry, and others won't.

The argument from ignorance: "desprecia cuanto ignora" as Machado would say.

4 mar 2006

2 mar 2006

One year ago today on Bemsha Swing I was criticizing Rexroth's Tu Fu. Now this seems much less objectionable to me than it did a year ago.

Some Articles I May Have Written or Planned to write

1. Apocryphal Lorca: The Reception of Spanish Language Poetry in the U.S.

2. Toward Thick Translation: English-Language Versions of Antonio Machado

3. Fragments of a Late Modernity: José Angel Valente and Samuel Beckett

4. Heriberto Yépez: Anglo-American Poetics Viewed From Across the Border

5. Jerome Rothenberg and the Ethnographic Sublime

Some Articles I Probably Won't Write

1. Ron Padgett: A Marxist-Leninist Approach

2. Silliman's Blog: The Early Years

1. Apocryphal Lorca: The Reception of Spanish Language Poetry in the U.S.

2. Toward Thick Translation: English-Language Versions of Antonio Machado

3. Fragments of a Late Modernity: José Angel Valente and Samuel Beckett

4. Heriberto Yépez: Anglo-American Poetics Viewed From Across the Border

5. Jerome Rothenberg and the Ethnographic Sublime

Some Articles I Probably Won't Write

1. Ron Padgett: A Marxist-Leninist Approach

2. Silliman's Blog: The Early Years

Sentences from student papers that make me want to tear my hair out:

"These two poems have various similarities and differences that it is important to compare and contrast." [or equivalent in Spanish]

Translation: "I am bored by this assignment; I am going through the motions until I graduate in three months. I can always fall back on my high-school training here, even though I am a senior in COLLEGE. Go Jayhawks! Muck Fizzou!"

"These two poems have various similarities and differences that it is important to compare and contrast." [or equivalent in Spanish]

Translation: "I am bored by this assignment; I am going through the motions until I graduate in three months. I can always fall back on my high-school training here, even though I am a senior in COLLEGE. Go Jayhawks! Muck Fizzou!"

1 mar 2006

At this point in my life and career there is a certain depth to my reading that should result in making my scholarship deeper too. It's partly a function of age, although not everyone of my age has it. Part of it is knowing how little you know. I thought I was moderately erudite when I was 30, but now I realize I'm not even close to being there now.

Another part of it is having gone to school with a number of different poets and writers. I read articles where I think that the critic has only read only a few things beyond what the teacher assigned.

(I'm not all that interested in being erudite in terms of information. We've all known erudite bores. I think of it as getting useable knowledge.)

Another part of it is being obsessive and somewhat competitive.

How many poets have followed Pound's curriculum? Troubadours, Calvacanti, Chinese poetry, Noh Theater? Quite a few. Now realize the difference between following it and coming up with it in the first place. If you really followed it you would know more than Pound, to paraphrase Bernstein on language poetry.

Rothenberg has that kind of depth too, obviously. Kenneth Koch had it, with different sources: Roussel, Noh Theater, Kawabata, Byron and Shelley, Borges. David Shapiro has it. Henry Gould has it. Irby has it. It's not a quietude issue, since this particular kind of depth doesn't line up with poetic styles.

Valente was a quite serious scholar of Spanish mysticism. Cernuda's book on British Romanticism turned out to be mostly just a pastiche. But imagine where he'd be if he hadn't even compiled the pastiche.

Superficiality bugs the hell out of me. But we are all superficial outside our domain. I've spent more than a few hours with Pierre's Celan translations, but my knowledge of Celan is still superficial.

Another part of it is having gone to school with a number of different poets and writers. I read articles where I think that the critic has only read only a few things beyond what the teacher assigned.

(I'm not all that interested in being erudite in terms of information. We've all known erudite bores. I think of it as getting useable knowledge.)

Another part of it is being obsessive and somewhat competitive.

How many poets have followed Pound's curriculum? Troubadours, Calvacanti, Chinese poetry, Noh Theater? Quite a few. Now realize the difference between following it and coming up with it in the first place. If you really followed it you would know more than Pound, to paraphrase Bernstein on language poetry.

Rothenberg has that kind of depth too, obviously. Kenneth Koch had it, with different sources: Roussel, Noh Theater, Kawabata, Byron and Shelley, Borges. David Shapiro has it. Henry Gould has it. Irby has it. It's not a quietude issue, since this particular kind of depth doesn't line up with poetic styles.

Valente was a quite serious scholar of Spanish mysticism. Cernuda's book on British Romanticism turned out to be mostly just a pastiche. But imagine where he'd be if he hadn't even compiled the pastiche.

Superficiality bugs the hell out of me. But we are all superficial outside our domain. I've spent more than a few hours with Pierre's Celan translations, but my knowledge of Celan is still superficial.

Suscribirse a:

Comentarios (Atom)